Difference between revisions of "Schrodinger equation"

(username removed) (Tidy up) |

(username removed) (Added section on time-independent equation and on one of the examples) |

||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

<math>i\hbar\frac{\partial}{\partial t}|\Psi\rangle=\hat H|\Psi\rangle</math> | <math>i\hbar\frac{\partial}{\partial t}|\Psi\rangle=\hat H|\Psi\rangle</math> | ||

| − | where <math>i</math> is the [[complex number|imaginary unit]] | + | where |

| + | :<math>i</math> is the [[complex number|imaginary unit]] | ||

| + | :<math>\hbar</math> is the [[Planck's constant|reduced Planck's constant]] | ||

| + | :<math>|\Psi\rangle</math> is the quantum mechanical state or wavefunction (expressed here in [[Dirac notation]]) | ||

| + | :<math>\hat H</math> is the [[Hamiltonian]] operator. | ||

The left side of the equation describes how the wavefunction changes with time; the right side is related to its energy. For the simplest case of a particle of mass m moving in a one-dimensional potential V(x), the Schrodinger equation can be written | The left side of the equation describes how the wavefunction changes with time; the right side is related to its energy. For the simplest case of a particle of mass m moving in a one-dimensional potential V(x), the Schrodinger equation can be written | ||

| Line 16: | Line 20: | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

| − | + | This can be expanded to give the three dimensional time dependent Schrodinger equation using the [[Laplacian|Laplacian operator]], <math>\nabla^2</math>: | |

| + | |||

| + | <math> | ||

| + | -\frac{\hbar^2}{2m} | ||

| + | \nabla^2 \Psi | ||

| + | +V(x)\Psi=i\hbar\frac{\partial \Psi}{\partial t} | ||

| + | </math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | In this case, the wavefunction is <math>\Psi(x,y,z,t)</math>. | ||

===Derivation=== | ===Derivation=== | ||

| Line 35: | Line 47: | ||

from which Schrodinger's equation and the eigenvalue problem <math> \hat H\Psi = E\Psi</math> can be easily seen. | from which Schrodinger's equation and the eigenvalue problem <math> \hat H\Psi = E\Psi</math> can be easily seen. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Time-independent Schrodinger Equation=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | The wavefunction is a multi-variable function, that is to say it depends on both [[time]] and space. Suppose that we have a function only in terms of space, <math>\psi(x)</math>. We can write the full wavefunction as <math>\Psi(x,t) = \psi(x) e^{-iEt/ \hbar}</math> for a state of definite energy. This type of state is also know as a "stationary state" as the probability distribution for this type of wavefunction over time is constant (see below). Substituting this wavefunction into the Schrodinger equation: | ||

| + | |||

| + | <math>- \frac{\hbar^2}{2m} \frac{\partial^2 \psi(x)}{\partial x^2} e^{-iEt/ \hbar} + V(x) \psi(x) e^{-iEt/ \hbar} = E \psi(x) e^{-iEt/ \hbar} </math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Cancelling the factor of <math>e^{-iEt/ \hbar}</math> results in a [[differential equation]] that only depends on <math>x</math>. This is the '''time-independent Schrodinger equation''': | ||

| + | |||

| + | <math>- \frac{\hbar^2}{2m} \frac{d^2 \psi(x)}{dx^2} + V(x) \psi(x) = E \psi(x)</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <math>\psi(x)</math> is often called the "wavefunction", though strictly speaking it is <math>\Psi(x,t)</math> that is the wavefunction. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Solutions to the Schrodinger Equation=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Solutions to the Schrodinger equation are known as "wavefunctions". However, for a solution to be physically valid, two conditions must be imposed on these solutions. These are that both the wavefunction and its first derivative must be [[Continuous function|continuous]]. Wavefunctions may be [[Real number|real]] or [[Complex numbers|complex]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Since the Schrodinger equation is [[Linear equations|linear]], if <math>\psi_1 (x)</math> and <math>\psi_2 (x)</math> are solutions, then <math>\psi_1 (x) + \psi_2 (x)</math> is also a solution. | ||

===Eigenvalue problems=== | ===Eigenvalue problems=== | ||

| Line 46: | Line 76: | ||

===Interpretation of the Wavefunction=== | ===Interpretation of the Wavefunction=== | ||

| − | The wavefunction is related to the probability of observing a particle at that location in space. More specifically, where the wavefunction has a greater value of <math>|\Psi|^2</math> at one location, a, compared to another, b, then the particle is more likely to be observed at a than b. | + | The wavefunction is related to the probability of observing a particle at that location in space. More specifically, where the wavefunction has a greater value of <math>|\Psi|^2</math> at one location, a, compared to another, b, then the particle is more likely to be observed at a than b. Note that the [[Absolute value|modulus] must be taken since the wavefunction may be [[Complex numbers|complex. |

====Normalisation==== | ====Normalisation==== | ||

| Line 64: | Line 94: | ||

For some wavefunctions, such as that of a free particle, the integral above does not exist and so they are said to be non-normalisable. | For some wavefunctions, such as that of a free particle, the integral above does not exist and so they are said to be non-normalisable. | ||

| − | ==Examples for the | + | ==Examples for the Time-Independent Equation== |

===Free particle in one dimension=== | ===Free particle in one dimension=== | ||

| − | In this case, <math>V(x)=0</math> | + | In this case, <math>V(x)=0</math>, the time-independent Schrodinger equation is: |

| + | |||

| + | <math>\frac{d^2 \psi}{dx^2} = - \frac{2mE}{\hbar^2} \psi</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | In this case, the solution is sinusoidal for some constants, <math>A</math>, <math>B</math>, <math>C</math>, and <math>D</math>: | ||

| − | <math>\psi= | + | <math>\psi=A \sin{kx} + B \cos{kx} = Ce^{ikx} + De^{-ikx}</math> |

| − | + | The [[energy]] can then be found as: | |

<math>E=\frac{\hbar^2 k^2}{2m}</math> | <math>E=\frac{\hbar^2 k^2}{2m}</math> | ||

| − | Physically, this corresponds to a wave travelling with a [[momentum]] given by <math>\hbar k</math>, where k can in principle take any value. | + | Physically, this corresponds to a wave travelling with a [[momentum]] given by <math>\hbar k</math>, where k can in principle take any value. This wavefunction is not normalisable. |

===Particle in a box=== | ===Particle in a box=== | ||

Consider a one-dimensional box of width a, where the potential energy is 0 inside the box and infinite outside of it. We can describe this potential by: | Consider a one-dimensional box of width a, where the potential energy is 0 inside the box and infinite outside of it. We can describe this potential by: | ||

| − | <math> | + | <math>V(x) = |

\begin{cases} | \begin{cases} | ||

\infty &\quad\text{if } x < 0\\ | \infty &\quad\text{if } x < 0\\ | ||

| Line 125: | Line 159: | ||

You may wonder what happens about the constant <math>B</math>. Since the Schrodinger equation is linear, <math>B</math> can take any value and the resulting wavefunction would be a solution. Since <math>|\psi (x)|^2</math> represents the probability of finding the particle at position <math>x</math> and across all space, this probability must equal 1, we can solve for <math>B</math>. We do this by integrating <math>|\psi (x)|^2</math> from <math>-\infty</math> to <math> + \infty</math>. Therefore the full solution is: | You may wonder what happens about the constant <math>B</math>. Since the Schrodinger equation is linear, <math>B</math> can take any value and the resulting wavefunction would be a solution. Since <math>|\psi (x)|^2</math> represents the probability of finding the particle at position <math>x</math> and across all space, this probability must equal 1, we can solve for <math>B</math>. We do this by integrating <math>|\psi (x)|^2</math> from <math>-\infty</math> to <math> + \infty</math>. Therefore the full solution is: | ||

| − | <math> | + | <math>V(x) = |

\begin{cases} | \begin{cases} | ||

\sqrt{\frac{2}{a}} \sin{\omega x} &\quad\text{if } x < 0\\ | \sqrt{\frac{2}{a}} \sin{\omega x} &\quad\text{if } x < 0\\ | ||

Revision as of 18:32, September 20, 2016

The Schrodinger equation is a linear differential equation used in various fields of physics to describe the time evolution of quantum states. It is the fundamental equation of non-relativistic quantum meachincs. The equation is named after its discoverer, Erwin Schrodinger.

Mathematical forms

General time-dependent form

The Schrodinger equation may generally be written

where

is the imaginary unit

is the imaginary unit is the reduced Planck's constant

is the reduced Planck's constant is the quantum mechanical state or wavefunction (expressed here in Dirac notation)

is the quantum mechanical state or wavefunction (expressed here in Dirac notation) is the Hamiltonian operator.

is the Hamiltonian operator.

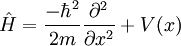

The left side of the equation describes how the wavefunction changes with time; the right side is related to its energy. For the simplest case of a particle of mass m moving in a one-dimensional potential V(x), the Schrodinger equation can be written

This can be expanded to give the three dimensional time dependent Schrodinger equation using the Laplacian operator,  :

:

In this case, the wavefunction is  .

.

Derivation

The quickest and easiest way to derive Schrodinger's equation is to understand the Hamiltonian operator in quantum mechanics. In classical mechanics, the total energy of a system is given by

where p is the momentum of the particle and V(x) is its potential energy. Applying the quantum mechanical operator for momentum:

and subbing into the classical mechanical form for energy, we get the same Hamiltonian operator in quantum mechanics:

from which Schrodinger's equation and the eigenvalue problem  can be easily seen.

can be easily seen.

Time-independent Schrodinger Equation

The wavefunction is a multi-variable function, that is to say it depends on both time and space. Suppose that we have a function only in terms of space,  . We can write the full wavefunction as

. We can write the full wavefunction as  for a state of definite energy. This type of state is also know as a "stationary state" as the probability distribution for this type of wavefunction over time is constant (see below). Substituting this wavefunction into the Schrodinger equation:

for a state of definite energy. This type of state is also know as a "stationary state" as the probability distribution for this type of wavefunction over time is constant (see below). Substituting this wavefunction into the Schrodinger equation:

Cancelling the factor of  results in a differential equation that only depends on

results in a differential equation that only depends on  . This is the time-independent Schrodinger equation:

. This is the time-independent Schrodinger equation:

is often called the "wavefunction", though strictly speaking it is

is often called the "wavefunction", though strictly speaking it is  that is the wavefunction.

that is the wavefunction.

Solutions to the Schrodinger Equation

Solutions to the Schrodinger equation are known as "wavefunctions". However, for a solution to be physically valid, two conditions must be imposed on these solutions. These are that both the wavefunction and its first derivative must be continuous. Wavefunctions may be real or complex.

Since the Schrodinger equation is linear, if  and

and  are solutions, then

are solutions, then  is also a solution.

is also a solution.

Eigenvalue problems

In many instances, steady-state solutions to the equation are of great interest. Physically, these solutions correspond to situations in which the wavefunction has a well-defined energy. The energy is then said to be an eigenvalue for the equation, and the wavefunction corresponding to that energy is called an eigenfunction or eigenstate. In such cases, the Schrodinger equation is time-independent and is often written

Here, E is energy, H is once again the Hamiltonian operator, and  is the energy eigenstate for E.

is the energy eigenstate for E.

One example of this type of eigenvalue problem is an electrons bound inside an atom.

Interpretation of the Wavefunction

The wavefunction is related to the probability of observing a particle at that location in space. More specifically, where the wavefunction has a greater value of  at one location, a, compared to another, b, then the particle is more likely to be observed at a than b. Note that the [[Absolute value|modulus] must be taken since the wavefunction may be [[Complex numbers|complex.

at one location, a, compared to another, b, then the particle is more likely to be observed at a than b. Note that the [[Absolute value|modulus] must be taken since the wavefunction may be [[Complex numbers|complex.

Normalisation

Wavefunctions are said to be "normalisable" if the following integral exists:

If that integral exists, then the wave function may be normalised by introducing a constant,  , such that

, such that

Note that  may be complex. This will produce and new wavefunction,

may be complex. This will produce and new wavefunction,  , which has the property that:

, which has the property that:

This is the probability of observing the particle between points a and b. For some wavefunctions, such as that of a free particle, the integral above does not exist and so they are said to be non-normalisable.

Examples for the Time-Independent Equation

Free particle in one dimension

In this case,  , the time-independent Schrodinger equation is:

, the time-independent Schrodinger equation is:

In this case, the solution is sinusoidal for some constants,  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  :

:

The energy can then be found as:

Physically, this corresponds to a wave travelling with a momentum given by  , where k can in principle take any value. This wavefunction is not normalisable.

, where k can in principle take any value. This wavefunction is not normalisable.

Particle in a box

Consider a one-dimensional box of width a, where the potential energy is 0 inside the box and infinite outside of it. We can describe this potential by:

This is also known as "the infinite square well".

This means that  must be zero outside the box. One can verify (by substituting into the Schrodinger equation) that

must be zero outside the box. One can verify (by substituting into the Schrodinger equation) that

is a solution if  where n is any integer. Thus, rather than the continuum of solutions for the free particle, for the particle in a box there is a set of discrete solutions with energies given by

where n is any integer. Thus, rather than the continuum of solutions for the free particle, for the particle in a box there is a set of discrete solutions with energies given by

Derivation

The particle cannot exits outside the box where the potential is infinite. Hence the wavefunction,  , here must be zero outside the box. Now let us consider inside the box. The Schrodinger equation inside the potential well becomes:

, here must be zero outside the box. Now let us consider inside the box. The Schrodinger equation inside the potential well becomes:

Rearranging this equation give

This has the same form as the basic equation for simple harmonic motion. Hence we can give the solution as

where  and

and  are unknown constants and

are unknown constants and  is equal to

is equal to  . To ind the value of the the constants, we substitute in boundary conditions. An additional constraint is that wavefunctions must be continious (they cannot suddenly change value). Hence

. To ind the value of the the constants, we substitute in boundary conditions. An additional constraint is that wavefunctions must be continious (they cannot suddenly change value). Hence

From this we can see that  must be zero. Using the continuous constraint again, we see that

must be zero. Using the continuous constraint again, we see that

The continuous constraint is only satisfied when  where

where  is an integer. We also note that

is an integer. We also note that  is not a solution as the wavefunction would be zero everywhere and so the probability of finding the particle is 0. We also discard solutions for

is not a solution as the wavefunction would be zero everywhere and so the probability of finding the particle is 0. We also discard solutions for  since these are not "new" solutions. As

since these are not "new" solutions. As  , these are just the negative of solutions with positive

, these are just the negative of solutions with positive  . By setting

. By setting  , we can find the energy

, we can find the energy  as:

as:

And so:

You may wonder what happens about the constant  . Since the Schrodinger equation is linear,

. Since the Schrodinger equation is linear,  can take any value and the resulting wavefunction would be a solution. Since

can take any value and the resulting wavefunction would be a solution. Since  represents the probability of finding the particle at position

represents the probability of finding the particle at position  and across all space, this probability must equal 1, we can solve for

and across all space, this probability must equal 1, we can solve for  . We do this by integrating

. We do this by integrating  from

from  to

to  . Therefore the full solution is:

. Therefore the full solution is:

where  is as above.

is as above.

Relativity

The Schrodinger equation is non-relativistic in nature. It can be re-derived taking special relativity into account. This results in the Klein-Gordon equation.