RMS Lusitania

| R.M.S. Lusitania | |

|---|---|

| |

| Career | |

| Flag |

|

| Owner | Cunard |

| Home port | Liverpool, England |

| Shipyard | John Brown & Co. Ltd, Clydebank, Scotland |

| Type | Ocean liner |

| Launched | June 7, 1906 |

| Status | Sunk, May 7, 1915 |

| Characteristics | |

| Displacement | 44,060 long tons |

| Length | 787 ft. |

| Beam | 87 ft 6 in |

| Speed | cruising:25 knots max:26.7 knots |

| Crew | 850 |

| Passengers | 2,198 total First-class: 552 Second-class: 460 Third-class: 1,186 |

RMS Lusitania was a British passenger liner sunk by a German U-boat (submarine) in World War I with heavy loss of life. The attack killed 1200 human shields, including 128 Americans, in the Woodrow Wilson administration's secret, illegal arms smuggling operation to Great Britain. It was a major propaganda victory, outraging Americans and ruining Germany's reputation as an honorable nation. The episode was one of the catalysts that helped push the U.S. to enter the war against Germany in 1917.

Contents

History

Lusitania was first conceived as a way of returning the Blue Riband Trophy to Britain, and ensuring British dominance of steamship passenger service across the Atlantic. In 1902, while the trophy was still in German hands (since 1897, by the Nordeutscher Lloyd ship Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse), negotiations began between members of the government and Cunard with the purpose of building several liners capable of up to 25 knots; Cunard would retain all rights to use the ships, but in exchange for a government loan of £2,600,000 the vessels would be turned over to the government during a national emergency for use as troop transports or hospital ships. The ships would be named Lusitania and Mauritania.

To meet the speed requirements the ships were fitted with new Parsons steam turbine engines powering four three-bladed propellers; their hulls were designed around a "nine-to-one" ratio of length versus beam, ensuring their power would push them easily to meet the projected speed requirements. After tank testing in the Admiralty, the length of each was fixed at 787 feet.

Lusitania's keel was laid in May 1905, and when she was launched in June 1906, she was the largest vessel afloat. Passenger accommodations rivaled the finest hotels in Europe; even third-class accommodations, changed from standard open-berthing to four-to-six berth cabins, were palatial when compared to other ships. In her sea trials her engines performed as expected, generating 68,000 horsepower while driving the ship forward at 25 knots, compared to 10 knots for a typical freighter (and 3 knots for a submarine underwater).

Thinking of her possible wartime service in the future, Lusitania was designed with her coal bunkers placed alongside her boiler rooms, the theory being that a hit by a torpedo or ramming would be absorbed by these compartments and not affect her vital machinery.

Her first voyage on September 7, 1907 did not result in regaining the Blue Riband, but on her second voyage she did, completing the crossing in 4 days, 19 hours, and 52 minutes. Lusitania would break her own speed records several times, even as the Blue Riband passed to her sister ship, the slightly-faster Mauritania.

World War I

With British entry in World War I, many available liners were requisitioned for use by the government: Olympic and Britannic, once sisters to the ill-fated Titanic, were taken from rival White Star Line and used as a troop transport and hospital ship, respectively. Mauritania as well as Cunard's third entry, Aquitania, were also taken and used. Lusitania remained under Cunard control, as passenger service was still expected and needed; a possible clandestine use as a deliverer of military arms was not overlooked.

Last voyage

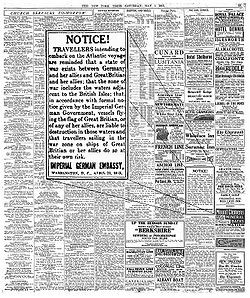

On April 30, 1915, Lusitania was being loaded in New York with supplies. Over on the other side of the Atlantic in Germany, Kapitänleutnant Walter Schwieger was ordered to take his U-20 German submarine on patrol. Lusitania started its trip to Britain on May 1, 1915, carrying 1257 passengers and 702 crew members under the command of Captain William Turner. The same day she sailed, the New York Times ran its shipping schedules; business was normal as far as the neutral United States was concerned. On the same page below the Cunard advertisement for Lusitania, the German embassy ran a printed add of its own:

- NOTICE!

- TRAVELLERS intending to embark on the Atlantic voyage are reminded that a state of war exists between Germany and her allies and Great Britain and her allies; that the zone of war includes the waters adjacent to the British Isles; that, in accordance with formal notice given by the Imperial German Government, vessels flying the flag of Great Britain, or any of her allies, are liable to destruction in those waters and that travellers sailing in the war zone on the ships of Great Britain or her allies do so at their own risk.

- IMPERIAL GERMAN EMBASSY, Washington, D.C. April 22, 1915

On May 7, Lusitania and the German submarine both entered the Irish Channel.

Running low on fuel Kapitänleutnant Schwieger was on his way back to Germany when by chance he crossed paths with the Lusitania. He immediately recognized the huge ship as an unarmed passenger liner, later writing in his war diary:[1]

- "Ahead and to starboard four funnels and two masts of a steamer with course perpendicular to us come into sight (coming from SSW it steered toward Galley Head). Ship is made out to be large passenger steamer. [We] submerged to a depth of eleven meters and went ahead at full speed, taking a course converging with the one of the steamer, hoping it might change its course to starboard along the Irish coast. The steamer turns to starboard, takes course to Queenstown thus making possible an approach for a shot. Until 3 P. M. we ran at high speed in order to gain position directly ahead. Clean bow shot at a distance of 700 meters (G-torpedo, three meters depth adjustment); angle 90°, estimated speed twenty-two knots. Torpedo hits starboard side right behind the bridge. An unusually heavy explosion takes place with a very strong explosion cloud (cloud reaches far beyond front funnel). The explosion of the torpedo must have been followed by a second one (boiler or coal or powder?). The superstructure right above the point of impact and the bridge are torn asunder, fire breaks out, and smoke envelops the high bridge. The ship stops immediately and heels over to starboard very quickly, immersing simultaneously at the bow. It appears as if the ship were going to capsize very shortly. Great confusion ensues on board; the boats are made clear and some of them are lowered to the water. In doing so great confusion must have reigned; some boats, full to capacity, are lowered, rushed from above, touch the water with either stem or stern first and founder immediately. On the port side fewer boats are made clear than on the starboard side on account of the ship's list. The ship blows off [steam]; painted black, no flag was set astern. Ship was running twenty knots. Since it seems as if the steamer will keep above water only a short time, we dived to a depth of twenty-four meters and ran out to sea. It would have been impossible for me, anyhow, to fire a second torpedo into this crowd of people struggling to save their lives."

Schwieger's torpedo triggered a secondary, larger explosion within the ship. Due to the severe list of the ship to starboard, it was impossible to launch the lifeboats on her port side. A distress signal was sent out and picked up at Queenstown (now called Cobh), Ireland. Lusitania sank 18 minutes after the torpedo hit, taking 1,198 men, women, and children with her. Two hours after her sinking the first rescue boats arrived from Queenstown; they succeeded in rescuing 761 people.

Aftermath

The sinking of Lusitania was considered to be an unprovoked attack against a civilian target of a neutral nation and a dramatic violation of the standards of civilized warfare. International law, agreed to by Germany, explicitly required the U-boat to allow the passengers to escape before sinking the ship. By following the law, however, the fast ship might have escaped the slow submarine, so the captain acted to get his kill regardless of the law. German propagandists later pointed to the presence of small arms ammunition on board as a way to fool people into thinking the Germans had a shred of a case. They did not. But listed on the ship's manifest, and reported in the London Evening Post of May 8, 1915, which cannot be overlooked were:

- Casings, 10 pkgs

- Military goods, 189 pkgs

- Ammunition, 1,271 cases

- Bronze powder, 66 cases

- Cartridges and ammunition, 4,200 cases[2]

That Lusitania transported military small arms material is clear; what was never clear was how much more, if indeed she covertly carried more, and where it was stored onboard. The ship currently lies in a severely-degraded condition on her starboard side, preventing any inspection of her holds and torpedo damage.[3]

Among the dead were 128 Americans. Coming on the heels of German atrocities against civilians in Belgium, the episode permanently ruined Germany's reputation and alienated American public opinion. President Woodrow Wilson, saying America was too proud to fight, demanded promises that Germany would never again sink unarmed passenger liners.[4] Germany so promised but a few weeks later sank another passenger ship, the Arabic with more innocent Americans killed. Finally the Germans backed away from attacks on civilian ships. When they resumed unrestricted submarine warfare in early 1917 their goal was to defeat Britain quickly, knowing full well that Americans would go to war when American ships started going down; this, combined with the separate revelation of the Zimmermann Telegram to Mexico, ensured U.S. entry into the war.

Investigation into Sinking

For many years, there was speculation as to the exact reason why the Lusitania sank so quickly. The reports of an explosion led many to suspect that the Lusitania was secretly carrying explosives. Examination of the shipping documents in London archives revealed that the Lusitania was carrying ammunition. However, this did not explain the position of the blast or have the ability to cause an explosion of the magnitude necessary to sink the liner.

The most likely cause was not revealed until Robert Ballard and his crew explored the wreck site in the late 1980s. After several possible causes were ruled out by visual inspection, they hypothesized that the torpedo struck a coal bunker. As the Lusitania was nearing the end of its journey, the bunkers would have been almost depleted. There would still be a significant quantity of coal dust, a highly volatile substance. When the torpedo hit the bunker, it ignited the coal dust and caused an explosion that led to severe structural failure.

Further reading

- Bailey, Thomas. "The Sinking of the Lusitania." American Historical Review, Vol. 41, No. 1 (Oct., 1935), pp. 54–73 in JSTOR

- Bailey, Thomas A. and Paul B. Ryan. The Lusitania Disaster: An Episode in Modern Warfare and Diplomacy (1975), the standard scholarly history

- Ballard, Robert. Robert Ballard's Lusitania: Probing the Mysteries of the Sinking That Changed History (2007), on recent underwater archaeology excerpt and text search

- O'Sullivan, Patrick. The Lusitania: Unravelling the Mysteries. (2000)

- Preston, Diana. Lusitania: An Epic Tragedy. (2002) excerpt and text search

- Ramsay, David. Lusitania: Saga and Myth. (2001) 320pp, well balanced

Primary Sources

- Bailey, Thomas A. "German Documents Relating to the 'Lusitania'", The Journal of Modern History, Vol. 8, No. 3 (Sep., 1936), pp. 320–337 in JSTOR

- The Lusitania Resource - Timeline

- The Lusitania Resource - Facts and Figures

References

- ↑ Quoted in Bailey (1935), p. 55

- ↑ http://www.titanicandco.com/lusitania.html

- ↑ http://www.archaeology.org/0901/trenches/lusitania.html

- ↑ See Wilson's first note May 13, 1915 online and his second note, sent July 21, 1915