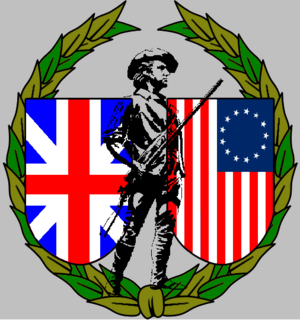

Battle of Cowpens

| Battle of Cowpens | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Overview | ||

| Date | January 17, 1781 | |

| Location | Cowpens, South Carolina | |

| Victor | Americans | |

| Combatants | ||

| United States | Loyalists | |

| Commanders | ||

| Daniel Morgan | Banastre Tarleton | |

| Casualties | ||

| 73 killed | 110 killed | |

The Battle of Cowpens occurred on January 17, 1781, during the American Revolution. American General Daniel Morgan ordered his line of militia to fire into British General Cornwallis' and Colonel Tarleton's soldiers, who included Highlanders, dragoons and loyalists. The British pursued the Americans, but American Continentals were waiting for the British over a hill. Mel Gibson's movie "The Patriot" depicted this battle.

The Americans scored a huge success, killing 110 British and capturing as many as 830.

Background

On December 2, 1780, Major General Nathanael Greene formally took command of the Southern Department of the Continental Army in Charlotte, North Carolina, succeeding Horatio Gates, who had been relieved following his disastrous defeat at the Battle of Camden in August. Since that battle, the American army had deteriorated badly in numbers, supplies, and morale; at the time Greene took over, it contained only about 2,500 soldiers, only a third of them properly equipped. In light of these poor conditions, Greene decided to withdraw from Charlotte to a more secure location on the Pee Dee River, where the army could reorganize; however, to avoid the appearance of retreating in the face of Cornwallis' army, he divided it into two segments that would stay in the area for the immediate future, one commanded by himself, the other by Morgan.

Greene's decision was a definite risk, as the American army, even united, was badly outnumbered by the British and could potentially be destroyed one small piece at a time. However, he reasoned that two small American forces could probably move faster than their more numerous opponents and could threaten the British positions in South Carolina from multiple directions. Greene would move southeast to threaten Charleston, while Morgan's detachment would harass Cornwallis' western garrisons at Ninety-Six and Augusta, Georgia. Morgan left Charlotte on December 20 with between 1100 and 1200 soldiers, marching first to Cheraw Hill and then into South Carolina.

Cornwallis' field army, with a strength of about four thousand men, was stationed at Winnsboro, South Carolina. Upon learning of Greene's maneuvers, he responded by dividing his force into three: the main body slowly advanced north; one detachment under Major General Alexander Leslie marched to Camden to defend against possible American attack; the third segment, under Tarleton, marched west against Morgan. Tarleton's small army was about equal to Morgan's in size, with some 1100 or so soldiers, although far more of them were trained regulars.

Battle

Morgan and Tarleton met on January 17 at Cowpens, a mostly open field just south of the Broad River that received its name from being a popular place to graze local cattle. At first glance, the location appeared to give the British every advantage: the lack of natural barriers to the west and east meant Morgan was in danger of being flanked on either side, while the Broad River was immediately in his rear and thus precluded an easy retreat. However, Morgan deliberately selected the site, later explaining that as many of his troops were poorly-disciplined militia, and thus prone to flee at the first opportunity, he felt it necessary to give battle on ground that offered no option of retreat. He also expected Tarleton, whose boldness and contempt for the enemy was well-known, to attempt a frontal assault, rather than a flanking maneuver.

To prepare for such an assault, Morgan deployed his soldiers in three lines: approximately 150 sharpshooters in front, followed by 300 militia under Andrew Pickens, positioned about 150 yards behind the first line, then a third line of 400 Continentals under John Howard, the same distance behind the militia, on the crest of a low hill; Morgan's reserve, about 100 cavalry under Major William Washington, was posted between the hill and the river. Morgan's instructions, which he personally explained to each of his men, were for the sharpshooters to deliver two volleys as the enemy approached, then fall back on Pickens' militia, who were to do the same before they in turn retreated around the left of Howard's Continentals and re-formed as an additional reserve, while the Continentals on the hill kept Tarleton pinned down.

The battle opened around sunrise, as Tarleton pushed his dragoons forward upon the first American line. The sharpshooters quickly repulsed the dragoons, inflicting about fifteen casualties; seeing this, Tarleton ordered an immediate attack by his infantry without taking time to study Morgan's position. As planned, the sharpshooters fell back on Pickens' militia, which fired two volleys at close range before themselves withdrawing to the left. Tarleton's infantry and dragoons charged the militia, but were briefly driven off by Washington's militia, which had ridden up from their position in the rear.

The resistance offered by the sharpshooters and militia had taken an unexpectedly heavy toll on the British. Morgan had ordered his men to take aim at officers in particular, who made up perhaps 40% of British casualties to this point. From this point on, Tarleton's troops were increasingly disorganized; nonetheless, they attacked Howard's Continentals making up the third line. As this assault developed, the 71st Highlanders were ordered to attack the American right flank; in response, Howard ordered a unit of Virginia militia on his right to face about at right angles to the main line and meet the flanking attempt. However, in the confusion of battle, these orders were misunderstood, and the militia marched to the rear. The entire line of Continentals, believing the rearward movement had been ordered, followed suit.

Morgan was initially outraged by the retreat, demanding of Howard, "Are you beaten?" To which Howard replied, "Do men who march like that look as though they were beaten?" In reality, though, the sudden withdrawal only completed the breakdown of order in the British ranks. Believing they were witnessing the beginning of a rout, the soldiers rushed forward in an undisciplined mass, rendering themselves prone to a counterattack. When the British were within thirty yards, Howard's men turned about and fired into their pursuers, the point-blank fire causing the line to break apart. The Continentals then launched a bayonet charge that overwhelmed the British center; simultaneously, Tarleton was flanked on the left by the re-formed American militia and on the right by Washington's cavalry. This double envelopment, described by many as a miniature reproduction of the Battle of Cannae, washed away the morale of the remaining British, most of whom quickly surrendered.

The only British unit to survive the debacle was the British Legion, under Tarleton's personal command, which fled the field after the main body surrendered. Tarleton himself barely escaped after nearly being apprehended by Washington at the close of the battle.

Aftermath

The Battle of Cowpens was a complete tactical victory for the Americans. Of the 1,100 or so soldiers in the British force opposing them, 712 (wounded and unwounded) were taken prisoner (though some put the figure as high as 830), in addition to about 110 killed. These casualties, which virtually wiped out Tarleton's brigade, represented a significant portion of Cornwallis' overall army, the more so as they occurred mostly among trained regulars he could hardly afford to lose. In addition, the battle marked a personal humiliation of Tarleton, who had gained a reputation as a bloodthirsty terror to the Patriots, and thus re-energized the American cause in the South. John Marshall noted the significance of the victory, writing: "Seldom has a battle, in which greater numbers were not engaged, been so important in its consequences as that of Cowpens."[1]

American casualties in the battle were much lower; Morgan reported only 73 killed and wounded. The battle plan Daniel Morgan developed for Cowpens has been much studied down the years, not only for its brilliance on paper, but also for how it played to the strengths rather than the weaknesses of his untested militia. Historian John Buchanan suggested that on this occasion, Morgan was "the only general in the American Revolution, on either side, to produce a significant original tactical thought."

In the wake of Cowpens, Cornwallis reassembled his men and chased the American army, which had reunited under Greene. He reached the Catawba River shortly after the Americans had crossed it. But a storm and flooded conditions then made the river impassable. Similar intervention by weather interfered with Cornwallis at the Yadkin River and Dan River.

British Commander Henry Clinton described this as follows: "Here the royal army was again stopped by a sudden rise of the waters, which had only just fallen (almost miraculously) to let the enemy over."

General Washington made a similar observation, "We have ... abundant reasons to thank Providence for its many favorable interpositions in our behalf. It has at times been my only dependence, for all other resources seemed to have failed us."

References

- ↑ The Life of George Washington : Commander in Chief of the American Forces, During the War Which Established the Independence of his Country, and First President of the United States, p. 401

External links

- The Hero of Cowpens: A Revolutionary Sketch, of Daniel Morgan and Benedict Arnold, 1885