Rattlesnake (American symbol)

The Rattlesnake, a reptile found only in the Americas, was the earliest use of an animal to symbolize the early colonies prior to the creation of the United States. First appearing in newspaper prints with the motto "Join or Die," by the time of the American Revolution the rattlesnake was frequently used in conjunction with the motto "Don't Tread on Me," becoming a common symbol for America, its independent spirit, and its resistance to tyranny.

Contents

First Use As Satire

In the mid-1700s, Britain had laws on its books which allowed for persons convicted of felonies to be transported across the Atlantic to her American colonies; from there these convicts were allowed to serve the remainder of their time or set loose. In a commentary published in the Pennsylvania Gazette on May 9, 1751, Benjamin Franklin used his sense of humor to prod at how bad an idea this was:

- "It has been said, that these Thieves and Villains introduc’d among us, spoil the Morals of Youth in the Neighbourhoods that entertain them, and perpetrate many horrid Crimes; But let not private Interests obstruct publick Utility. Our Mother knows what is best for us. What is a little Housebreaking, Shoplifting, or Highway Robbing; what is a Son now and then corrupted and hang’d, a Daughter debauch’d and pox’d, a Wife stabb’d, a Husband’s Throat cut, or a Child’s Brains beat out with an Axe, compar’d with this 'Improvement and well peopling of the Colonies!'"

Franklin's suggestion was to let the mother country know how the colonists felt about this, and a large amount of rattlesnakes sent in return and released in public parks would make an even trade:

- "In the Spring of the Year, when they first creep out of their Holes, they are feeble, heavy, slow, and easily taken; and if a small Bounty were allow’d per Head, some Thousands might be collected annually, and transported to Britain. There I would propose to have them carefully distributed in St. James’s Park, in the Spring-Gardens and other Places of Pleasure about London; in the Gardens of all the Nobility and Gentry throughout the Nation; but particularly in the Gardens of the Prime Ministers, the Lords of Trade and Members of Parliament; for to them we are most particularly obliged...I would only add, That this Exporting of Felons to the Colonies, may be consider’d as a Trade, as well as in the Light of a Favour. Now all Commerce implies Returns: Justice requires them: There can be no Trade without them. And Rattle-Snakes seem the most suitable Returns for the Human Serpents sent us by our Mother Country. In this, however, as in every other Branch of Trade, she will have the Advantage of us. She will reap equal Benefits without equal Risque of the Inconveniencies and Dangers. For the RattleSnake gives Warning before he attempts his Mischief; which the Convict does not."

"Join or Die"

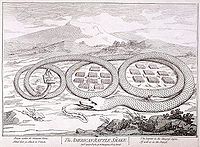

The famous cartoon entitled "Join, or Die," printed on 9 May 1754, again by Franklin in the Pennsylvania Gazette, shows a sliced up rattlesnake that forms a map of the colonies. The cartoon alludes to an old myth that a snake that had been cut into pieces would come back to life if the sections were reassembled before sunset, with Frankin intending that his cartoon was an allegory for the need of all the colonies to be united against France during the French and Indian War then being fought. Franklin based his cartoon on a 17th-century French emblem book by Nicolas Verrien which includes a snake divided into two parts with the motto: Se rejoindre ou mourir ('Join or die').

While the idea behind the illustration was Franklin's, historians have not discovered who did the actual engraving. In form the illustration follows the plan of an emblem book illustration, with a motto, a symbolic picture, and an explanatory text; Franklin even referred to it in correspondence as an "emblem." Franklin was responsible for many visual creations, such as cartoons, designs for flags and paper money, emblems and devices. He possessed an extraordinary knowledge of symbols and heraldry. The snake image may be a composite of those found in Mark Catesby's The Natural History of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahama Islands (1731–43). The iconic image of national unity became widespread in political illustrations concerning the Stamp Act of 1765, the American Revolution, and years later during the American Civil War.[1]

American Revolution

After the French and Indian War had ended, Britain decided that the American colonists should bear the bulk of the burden for paying it, and the Stamp Act of 1765 caught the colonists by surprise, who felt that they were just as British as the mother country and should not be taxed without their consent. In response to the demand for taxation Colonel Isaac Barre, a member of the British parliament and a champion of colonists' rights, stated "They nourished up by your indulgence! They grew up by your neglect of them. As soon as you begin to care about them, that care was exercised in sending persons to rule them in one department and another, . . . men whose behavior on many occasions has caused the blood of those Sons of Liberty to recoil within them." [1] Taking their name from his speech, the Sons of Liberty would show increasing resentment and hostility toward British rule in the years following up to the American Revolution; among them was silversmith and engraver Paul Revere, who had published in the Massachusetts Spy newspaper a cartoon of a dragon (symbolizing Britain) being attacked by a rattlesnake in 1774. By then, Franklin's earlier "Join or Die" cartoon took on new meaning as a united colonist front against Great Britain herself.

After the Battle of Bunker Hill in the fall of 1775, several British merchant ships were captured, along with their stores of badly-needed gunpowder. The Continental Congress also decided that the ships captured would form the nucleus of a new navy, and authorised the mustering of marines to accompany the ships. One company of marines in Philadelphia marched beating drums bearing the image of a coiled rattlesnake on a yellow background, above the motto "Don't tread on me" [2]. In Pennsylvania Journal on December 27, 1775 a letter by a man who signed it "The American Guesser" (and possibly determined to have been Franklin) mentioned this image:

- "I observed on one of the drums belonging to the marines now raising, there was painted a Rattle-Snake, with this modest motto under it, "Don't tread on me." As I know it is the custom to have some device on the arms of every country, I supposed this may have been intended for the arms of America; and as I have nothing to do with public affairs, and as my time is perfectly my own, in order to divert an idle hour, I sat down to guess what could have been intended by this uncommon device — I took care, however, to consult on this occasion a person who is acquainted with heraldry, from whom I learned, that it is a rule among the learned of that science "That the worthy properties of the animal, in the crest-born, shall be considered," and, "That the base ones cannot have been intended;" he likewise informed me that the ancients considered the serpent as an emblem of wisdom, and in a certain attitude of endless duration — both which circumstances I suppose may have been had in view. Having gained this intelligence, and recollecting that countries are sometimes represented by animals peculiar to them, it occurred to me that the Rattle-Snake is found in no other quarter of the world besides America, and may therefore have been chosen, on that account, to represent her." [3]

Culpeper Minute Men

Mustering in Virginia were men who formed the First Virginia Regiment, a militia of three hundred men under the command of Colonel Patrick Henry, who had just delivered a fiery speech in the colonial legislature proclaiming "give me liberty, or give me death!" Approximately one hundred of these men were from the town of Culpeper, which struck a fearful pose as they marched, wearing the dress of marauders in buckskin with Henry's words printed on their chests, tomahawks and knives in their belts, and a white flag flying above them with the image of a coiled rattlesnake above the now-familiar "Don't tread on me" motto. Culpeper County historian Eugene Scheel wrote of them:

- "Their flag was special. Philip Slaughter described its central symbol as a coiled rattlesnake about to strike, and below it the words 'Don't tread on me!' At each side was the inscription 'Liberty of Death!' - those words of Patrick Henry, spoken that March at the second Virginia revolutionary convention. At the flag's top was the inscription 'The Culpeper Minute Men.' Benjamin Franklin had used the snake, cut into pieces, in his 1754 'Join, or Die' cartoon, and continued use of the serpent in newspapers in the post-1765 period undoubtedly prompted the Culpeper banner. The flag appears to predate the more famous Rhode Island rattlesnake banner presented by Col. Christopher Gadsden to the South Carolina Provincial Congress in February, 1776, and is contemporaneous with the Fifth Pennsylvania Regiment rattlesnake flag. Both these banners also bore the words 'Don't tread on me.'" (Scheel, pg. 55)

Gadsden Flag

For a more detailed treatment, see Gadsden Flag.

- "Col. Gadsden presented to the Congress an elegant standard, such as is to be used by the commander in chief of the American navy; being a yellow field, with a lively representation of a rattle-snake in the middle, in the attitude of going to strike, and these words underneath, "DON'T TREAD ON ME!" (Journal of the South Carolina Provincial Congress, 9 February 1776)

Colonel Christopher Gadsden was a member of the Continental Congress who represented South Carolina, a member of the Sons of Liberty in that colony, and on the Marine Committee during the outfitting of the new Continental Navy. During the Age of Sail a squadron commander flew three flags from his ship: the "jack" (a flag placed at the bow); the "standard" (a personal flag flown from the main masthead); and the "ensign" (the national flag, flown from the stern). There is some debate as to whether of not a striped flag bearing the image of a rattlesnake was ever flown from an American warship during the Revolution; period engravings suggest that such a flag did exist and was used. Commodore Esek Hopkins, the first and only commander of the Continental Navy and chosen for that position by Colonel Gadsden, flew as his personal standard Gadsden's flag; the Grand Union Flag, a thirteen-striped flag with the colors of the British Union in the canton, served as the national ensign.

The only written description of the Continental Navy jack contemporary with the American Revolution appears in Commodore Hopkins's "Signals for the American Fleet," January 1776, where it is described as "the strip'd jack." No document says that the jack had a rattlesnake or motto on it. Elsewhere, Hopkins mentions using a "striped flag" as a signal. Since American merchant ships often displayed a simple red and white striped flag, there is a good chance that the striped jack to which Hopkins refers was the plain, striped flag used by American merchant ships.

But engravings also show Hopkins standing before one of his ships, and on the stern post is a large, striped flag bearing a rattlesnake uncoiled diagonally across. This fact seems to have been confirmed by Benjamin Franklin, who wrote a description of the early American fleet to the Ambassador to Naples, describing that "Some of the States have Vessels of War, distinct from those of the United States. For Example, the Vessels of War of the State of Massachusetts Bay have Sometimes a Pine Tree, and South Carolina a Rattlesnake in the Middle of the thirteen Stripes."

The normal jack flown from U.S. Navy warships is essentially the canton of the national ensign. The First Navy Jack was revived in 1980: an instruction from the Secretary of the Navy (SECNAV Instruction 10520.4) directed that the commissioned ship having the longest continuous period of commissioned active duty would have the honor of flying that flag until decommissioned, whereby the jack would be transferred to the next such vessel. This was changed during the Global War on Terrorism in 2002 (SECNAV Instruction 10520.6), when the Secretary directed that all ships fly the First Navy Jack. The First Navy Jack was discontinued in 2019.[2]

Use Today

During the American revolutionary period, persons who protested heavy taxation or other abuses committed by the Crown were subject to arbitrary arrest and imprisonment, often without trial; these abuses were written down in the Declaration of Independence, and prevented by the Bill of Rights in the United States Constitution. However, today's American government has saw fit to label tax protestors - along with Christians, pro-life people, and Second Amendment supporters - as "right wing terrorists" [4]. Among those targeted are those who fly the image of the rattlesnake; in one incident a man was stopped on a Louisiana road and investigated for "extremist activities" simply for having the Gadsden flag as part of his bumper sticker [5].

All three flags were among those flown at the Tax Day Tea Party across the country on April 15, 2009, in protest of President Barack Obama's massive $1.3 trillion stimulus bill. They have since appeared, as well, at other events connected with the Tea Party Movement and other similar movements such as Texit.

See also

- Flag of the United States of America

- Confederate States of America

- American historical flags

- Gadsden Flag

References

- ↑ Karen Severud Cook, "Benjamin Franklin and the Snake that would not Die," British Library Journal 1996 22 (1): 88-112. 0305-5167; Mark Bryant, "The First American Political Cartoon," History Today v. 57#12 (December 2007) pp 58+. online edition

- ↑ Read, Russ (July 20, 2019). 'Don't Tread On Me' flag has long history of Navy use. Washington Examiner. Retrieved July 20, 2019.

Notes

- Franklin, Benjamin. "Felons and Rattlesnakes", commentary printed in The Pennsylvania Gazette, May 9, 1751.

- Franklin, Benjamin. "The American Commissioners to [Domenico Caracciolo]" (personal letter), dated October 9, 1778

- Scheel, Eugene M, and Culpeper Historical Society, Inc. Culpeper: A Virginia County's History Through 1920; Green Publishers, Inc., Orange, Virginia (1982)

| |||||||||||||||||