Difference between revisions of "George Bernard Shaw"

m (→Eugenics) |

(Wanted US Constitution abolished) |

||

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

After reading the first Fabian tract, ''[http://lib-161.lse.ac.uk/archives/fabian_tracts/001.pdf Why are the many poor?]'' in 1884, Shaw joined the [http://www.fabians.org.uk/ Fabian Society], which, he wrote, "set up the banner of Socialism militant."<ref>G. Bernard Shaw, "[http://walterschafer.com/fabiansocietyhistory.htm Fabian Tract No. 41: The Fabian Society, Its Early History]," (Fabian Society Reprint, 1899)</ref> He began writing Fabian tracts, and personally converted [http://encyclopedia.farlex.com/Sidney+Webb Sidney Webb] to socialism, recruiting him into the Fabian Society.<ref>[[#refHenderson1911| Henderson 1911]]: 102-106.</ref> | After reading the first Fabian tract, ''[http://lib-161.lse.ac.uk/archives/fabian_tracts/001.pdf Why are the many poor?]'' in 1884, Shaw joined the [http://www.fabians.org.uk/ Fabian Society], which, he wrote, "set up the banner of Socialism militant."<ref>G. Bernard Shaw, "[http://walterschafer.com/fabiansocietyhistory.htm Fabian Tract No. 41: The Fabian Society, Its Early History]," (Fabian Society Reprint, 1899)</ref> He began writing Fabian tracts, and personally converted [http://encyclopedia.farlex.com/Sidney+Webb Sidney Webb] to socialism, recruiting him into the Fabian Society.<ref>[[#refHenderson1911| Henderson 1911]]: 102-106.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==United States Constitution== | ||

| + | Bernard Shaw believed the Constitution ought to be abolished, as it kept getting in the way of [[FDR]]. | ||

| + | {{cquote|I told you what to do and you haven't done it. And you're up to your neck in trouble, in consequence. I told you in New York. I put it to you very carefully and exactly. I told you that what you had to do in this country was to abolish your constitution, which was preventing you from doing anything. And now you see what's happened since. Every attempt you've made to do anything the Supreme Court immediately stops it and says it's against the constitution. | ||

| + | <p>Well, I tell you again to get rid of your Constitution. But I suppose you won't do it. You have a good president and you have a bad Constitution, and the bad Constitution gets the better of the good President all the time. The end of it will be is that you might as well have an English Prime Minister.<ref>[https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a0Pk0NUiw2o (Rare!) Various Scenes with George Bernard Shaw (1931 Fox Movietone Newsreel)]</ref>}} | ||

===Stalinism=== | ===Stalinism=== | ||

Revision as of 17:05, April 25, 2015

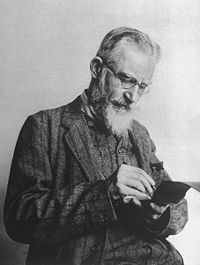

George Bernard Shaw (known as Bernard Shaw or GBS) (1856-1950) was an Irish writer, playwright and music and drama critic, born in Dublin. He was a lifelong socialist and a member of the Fabian Society. He was also a proponent of eugenics.[1] Many of his plays had social themes, including Major Barbara and Pygmalion; the latter was the inspiration for the musical My Fair Lady. Also among his many plays were Arms and the Man, The Devil's Disciple and Saint Joan. In 1925 he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature.

Contents

Religion

As a child Shaw attended the Church of Ireland, an autonomous province of the Anglican Communion. Until he was thirty or so, Shaw called himself an atheist. He became one, he later quipped, before he could think.[2] In the 1890s, Shaw repudiated atheism. In his 1931 play, "Too True to be Good," One of Shaw's characters delivers a speech sometimes taken to be Shaw's own view:

| “ | THE ELDER [rising impulsively] Determinism is gone, shattered, buried with a thousand dead religions, evaporated with the clouds of a million forgotten winters. The science I pinned my faith to is bankrupt: its tales were more foolish than all the miracles of the priests, its cruelties more horrible than all the atrocities of the Inquisition. Its spread of enlightenment has been a spread of cancer: its counsels that were to have established the millennium have led straight to European suicide. And I—I who believed in it as no religious fanatic has ever believed in his superstition! For its sake I helped to destroy the faith of millions of worshippers in the temples of a thousand creeds. And now look at me and behold the supreme tragedy of the atheist who has lost his faith—his faith in atheism, for which more martyrs have perished than for all the creeds put together.[3] | ” |

But in renouncing materialism, Shaw did not embrace theism, but Nietzschean "Vitalism." Shaw proselytized a mystical "Life Force," which he regarded as an impersonal "will" manifested in the sex drive and evolution, leading toward the development of god in the form of a Nietzschean "Superman."[4] In a 1907 lay sermon at Kensington Town Hall in London, Shaw exhorted:

| “ | When you are asked, "Where is God? Who is God?" stand up and say, "I am God and here is God, not as yet completed, but still advancing towards completion, just in so much as I am working for the purpose of the universe, working for the good of the whole of society and the whole world, instead of merely looking after my personal ends."[5] | ” |

"In truth, Shaw didn’t believe in an existing God at all," concludes Gary Sloan. "What he believed was that evolution, eons hence, will produce a godlike race in which the life force will consummate its quest for godhead."[6]

Politics

Shaw began his education by reading John Stuart Mill, August Comte, Charles Darwin and Herbert Spencer, and was converted to socialism by Henry George's Progress and Poverty. Moving on to Karl Marx's Das Kapital, he began preaching socialism with the utmost zeal and enthusiasm[7] at socialist rallies, or just standing on soapboxes at Speaker's Corner in London's Hyde Park.[8]

After reading the first Fabian tract, Why are the many poor? in 1884, Shaw joined the Fabian Society, which, he wrote, "set up the banner of Socialism militant."[9] He began writing Fabian tracts, and personally converted Sidney Webb to socialism, recruiting him into the Fabian Society.[10]

United States Constitution

Bernard Shaw believed the Constitution ought to be abolished, as it kept getting in the way of FDR.

| “ | I told you what to do and you haven't done it. And you're up to your neck in trouble, in consequence. I told you in New York. I put it to you very carefully and exactly. I told you that what you had to do in this country was to abolish your constitution, which was preventing you from doing anything. And now you see what's happened since. Every attempt you've made to do anything the Supreme Court immediately stops it and says it's against the constitution.

Well, I tell you again to get rid of your Constitution. But I suppose you won't do it. You have a good president and you have a bad Constitution, and the bad Constitution gets the better of the good President all the time. The end of it will be is that you might as well have an English Prime Minister.[11] |

” |

Stalinism

At the invitation of Stalin, Shaw visited the Soviet Union[12] in 1931, at age 75.[13] He became a loyal apologist for Stalinism, reporting the Gulag to be a kind of luxury vacation spa, its large population due solely to "the difficulty of inducing [prisoners] to come out... As far as I could make out they could stay as long as they liked."[14] On the last day of his pilgrimage, he said, "Tomorrow I leave this land of hope and return to our Western countries of despair."[15]

In 1933, Shaw wrote a Letter to the Editor of the Manchester Guardian, denouncing Malcolm Muggeridge's exposé of Stalin's Terror Famine as a "lie" and a "slander"; the following year he published a 16,000-word apologia for Stalin's mass murders, in which he expressed sympathy for the "unfortunate Commissar" who "found himself obliged to put a pistol in his pocket and with his own hand shoot" disobedient workers, "so that he might the more impressively ask the rest of the staff whether they yet grasped the fact that orders are meant to be executed." Shaw went on to attack the rule of law, in favor of the arbitrary rule of men, adding:

| “ | [T]he most elaborate code of [law]... would still have left unspecified a hundred ways in which wreckers of Communism could have sidetracked it without ever having to face the essential questions: are you pulling your weight in the social boat? are you giving more trouble than you are worth? have you earned the privilege of living in a civilized community? That is why the Russians were forced to set up an Inquisition or Star Chamber, called at first the Cheka and now the Gay Pay Oo (Ogpu), to go into these questions and "liquidate" persons who could not answer them satisfactorily.[16] | ” |

In 1936, Shaw publicly defended Stalin's Great Terror, saying, “Even in the opinion of the bitterest enemies of the Soviet Union and of her government, the [purge] trials have clearly demonstrated the existence of active conspiracies against the regime... I am convinced that this is the truth, and I am convinced that it will carry the ring of truth even in Western Europe, even for hostile readers.”[17] Shaw likewise defended Stalin's mass executions, scolding, "we cannot afford to give ourselves moral airs when our most enterprising neighbor... humanely and judiciously liquidates a handful of exploiters and speculators..."[18]

In 1948, Shaw said:

| “ | I am a communist, but not a member of the Communist Party. Stalin is a first rate Fabian. I am one of the founders of Fabianism and as such very friendly to Russia.[19] | ” |

In 1949, he repeated the point, writing, "I am a Communist and always call myself so." The British Communist Party had blundered in failing to tell British voters that, according to Shaw, "in Russia, private enterprise flourishes more than ever." He also argued that the Communists should support the Marshall Plan, which, he said, "is for the moment absolutely necessary."[20] That year Shaw even wrote a defense of Stalin's pseudo-scientific Lysenkoism.

Eugenics

In addition to socialism, Shaw was an advocate of eugenics. "Extermination must be put on a scientific basis if it is ever to be carried out humanely and apologetically as well as thoroughly," he wrote. "[I]f we desire a certain type of civilization and culture we must exterminate the sort of people who do not fit into it."[21] In one public address, recorded in a March 5, 1931 newsreel, Shaw gave expression to the Nazi doctrine of "life unworthy of life" (Lebensunwertes Leben):[22]

| “ | You must all know half a dozen people at least who are no use in this world, who are more trouble than they are worth. Just put them there and say Sir, or Madam, now will you be kind enough to justify your existence?

If you can’t justify your existence, if you’re not pulling your weight, and since you won't, if you’re not producing as much as you consume or perhaps a little more, then, clearly, we cannot use the organizations of our society for the purpose of keeping you alive, because your life does not benefit us and it can’t be of very much use to yourself.[23] |

” |

One of Shaw's long-term obsessions was mass murder by means of poison gas. In a 1910 lecture before the Eugenics Education Society, he said:

| “ | We should find ourselves committed to killing a great many people whom we now leave living... A part of eugenic politics would finally land us in an extensive use of the lethal chamber. A great many people would have to be put out of existence simply because it wastes other people's time to look after them.[24] | ” |

In the BBC's weekly magazine, Shaw made a 1933 "appeal to the chemists to discover a humane gas that will kill instantly and painlessly. Deadly by all means, but humane not cruel..."[25] His appeal would shortly come to fruition in Nazi Germany. As Robert Jay Lifton notes in The Nazi Doctors, "The use of poison gas—first carbon monoxide and then Zyklon B—was the technological achievement permitting 'humane killing.'"[26]

Shaw admired not just Stalin, but Mussolini and even Hitler.[27] He despised freedom, writing, "Mussolini... Hitler and the rest can all depend on me to judge them by their ability to deliver the goods and not by... comfortable notions of freedom."[28]

In the midst of the Battle of Britain, when the Wehrmacht, having routed the British at Dunkirk, was poised on the English Channel and the Luftwaffe was bombing London nightly, Shaw was asked what he would do if he were Prime Minister, if the Nazis invaded. Shaw replied, "Welcome them as tourists."[29]

Shaw has also been criticized as anti-Semitic: he once exhorted Jews to "stop being Jews and start being human beings."[30]

Unlike most eugenicists, who recoiled in horror from the implications of eugenics after World War II, when the horrors of Nazism were exposed to the world, Shaw continued to advocate it, writing in 1948 that we should enslave “a considerable class of persons” who, according to him, “cannot fend for themselves.” Placed under “tutelage, superintendence, and provided sustenance,” such people, says Shaw, “make good infantry soldiers and well-behaved prisoners.” His prescription: “Reorganize their lives for them; and do not prate foolishly about their liberty.”

Shaw continued to advocate mass murder, calling it “kindly but ruthless judicial liquidation” -- not for murderers, but for “the criminal you cannot reform” –- career criminals, even those who commit petty crimes.

In addition to recidivists, the death penalty should be applied, he wrote, to “idiots” and “morons”: “Do not punish them. Kill, kill, kill, kill, kill them.” Shaw admitted that most of these people are “quite incapable of committing a murder,” but argued that “the increase or decrease of crime is not the point at issue.” They should be killed, according to Shaw, simply because they are incapable of “paying their way.”

Clarifying that he was advocating mass murder, Shaw added that “on this principle we shall liquidate many more human nuisances than at present if we are to the weed the garden thoroughly.”

Most ominously, among those Shaw marked for death were people he called “ungovernables” and those who are incapable, according to Shaw, of “discharging their social duties.” (These labels perhaps cover those who do not acquiesce to slavery and mass murder.)[31]

References

- ↑ University of Florida; Language of eugenics

- ↑ Sloan 2004

- ↑ Bernard Shaw, "Too True to be Good," (Samuel French, Inc., 1935) ISBN 0573601518, p. 99

- ↑ George Bernard Shaw, Act III: "Don Juan in Hell," Man and Superman (Brentano's, 1916), pp. 71-142

- ↑ George Bernard Shaw, "The New Theology," Christian Commonwealth, May 23 and 27, 1907

- ↑ Sloan 2004

- ↑ Henderson 1911: 102-104.

- ↑ Mazer

- ↑ G. Bernard Shaw, "Fabian Tract No. 41: The Fabian Society, Its Early History," (Fabian Society Reprint, 1899)

- ↑ Henderson 1911: 102-106.

- ↑ (Rare!) Various Scenes with George Bernard Shaw (1931 Fox Movietone Newsreel)

- ↑ Mazer

- ↑ "Review: The Lure of Fantasy: Bernard Shaw, Volume III, by Michael Holroyd," The Economist, October 26, 1991

- ↑ Hollander 1998: 146

- ↑ Hollander 1998: 38-39

- ↑ Shaw 1933

- ↑ Arnold Beichman, "Death of the Butcher," Hoover Digest, 2003 No. 2

- ↑ Hollander 1998: 152-153

- ↑ Evening Herald (Dublin, Ireland), February 3, 1948, reprinted in Economic Council Letter (National Economic Council), Issue 278, Part 397 (1952), p. 290

- ↑ "People," Time magazine, March 21, 1949

- ↑ Shaw 1933

- ↑ Dr. Stuart D. Stein, "Life Unworthy of Life" and other Medical Killing Programmes, University of the West of England

- ↑ Edvins Snore, The Soviet Story (Clip)

- ↑ The Daily Express (London), March 4, 1910, quoted in Dan Stone, Breeding Superman: Nietzsche, Race and Eugenics in Edwardian and Interwar Britain (Liverpool University Press, 2002) ISBN 0853239975

- ↑ The Listener (London), February 7, 1934

- ↑ Robert Jay Lifton, The Nazi Doctors: Medical Killing and the Psychology of Genocide (Basic Books, 1986) ISBN 0465049052, p. 453

- ↑ "Shaw Heaps Praise Upon the Dictators: While Parliaments Get Nowhere, He Says, Hitler, Mussolini and Stalin Do Things," From an Address By George Bernard Shaw, The New York Times, December 10, 1933

- ↑ Hollander 1998: 169

- ↑ Thomas Sowell, "Pacifism and war," Jewish World Review, September 24, 2001 (7 Tishrei, 5762)

- ↑ Shaw Society of America, The Shaw review, Volumes 3-4 (Pennsylvania State University Press, 1960), p. 13

- ↑ George Bernard Shaw, "Capital Punishment," The Atlantic, June 1948.

External Links

- George Bernard Shaw Biography and works at The Literature Network

- What Liberals Say - George Bernard Shaw, Accuracy In Media

- Gary Sloan, "The Religion of George Bernard Shaw: When Is an Atheist?," American Atheist, Autumn 2004

- Archibald Henderson, George Bernard Shaw: His Life and Works (Cincinnati: Stewart & Kidd, 1911) ISBN 1417961775

- Cary M. Mazer, Bernard Shaw: a Brief Biography, University of Pennsylvania

- Paul Hollander, Political Pilgrims: Western Intellectuals in Search of the Good Society (New Brunswick, N.J: Transaction Publishers, 1998) ISBN 1560009543

- George Bernard Shaw, Preface, "On the Rocks" (1933)